|

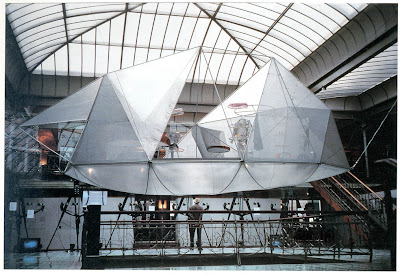

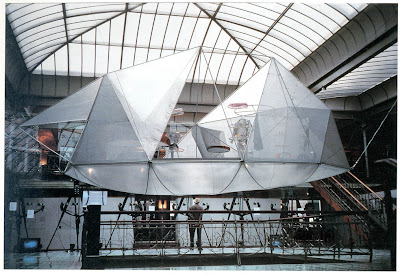

| Pao 2, Dwelling for a Tokyo Nomad Woman - Toyo Ito |

The debate over the nature of society in the late 20th century and the emerging conceptions of a 'hypermodernism' (Tafuri, Virilio), 'reflexive modernity' (Giddens, Beck, Lash), or broadly a 'postmodern condition', generally revolve around the critique of modernism's inflexibility in the face of contingency and ambiguity. These theories respond to measurable changes in the institutions of modern society, particularly to the effects of globalization. Globalization is a complex phenomenon which has diverse impacts but I think there is an interesting urban dynamic that emerges from the economic process of decomposition.

One of the major impacts of economic globalization is the decomposition of national economies into a decentralized system of world trade. Sites of production have been relocated from developed nations to the developing nations to take advantage of low cost labor. Different levels of production--for instance assembly--have emerged in separate regions from specialized manufacturing, R&D, and marketing. Much of this is fueled by efficient logistics and instantaneous networked communications. The decomposition of industries is mirrored in the division of nations into regions of production and consumption. The emergence of high-tech manufacturing and a strong service and financial sector in post-war Japan placed it in the camp of consumer nations along with the west.

The intensification of consumerism in the late 20th century led to descriptions of a society of individuals crafting their identities based on their patterns of consumption--based on the things they buy. This was a theme that Toyo Ito responded to when he designed his

Pao, or

Dwellings for a Tokyo Nomad Woman. Tokyo of the 1980's was one of the densest and technologically advanced cities in the world. High real estate prices and a hyperactive culture industry created a city that was itself decomposing.

|

| Pao 1, Dwelling for a Tokyo Nomad Woman - Toyo Ito |

The typical urban lifestyle exemplified by Ito's 'nomad girl' meandered from work, to places of entertainment, restaurants, and shopping before returning to a residence that was little more than a sleeping quarters. As Iñaki Abalos and Juan Herreros put it: "The nomad girl does not act or pressure the environment, but rather is prepared to be the object herself of the actions and offers proposed by consumerism."[1] Ito responds to this metaphorical nomadic lifestyle by proposing an architecture that is characterized by its ephemeral yet permanent nature, a thinness and lightness. He approaches the surfaces in his designs as sites for the intersection of real and virtual space through projection. This dematerialization or de-emphasis of the architecture must have had an impact on one of Ito's more prominent apprentices, Kazuyo Sejima.

Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa's approach to architecture (as SANAA) borrows some elements from Ito's, and concentrates them. Their visual language is ostensibly minimalist, abstract, and indeterminate. However, these characteristics provide a space for extension: "Blankness calls for active projection, indeterminacy asks for participation, and the absence of spatial hierarchy requires communal initiative."[2] Matthew Allen discerns a two-part mode of curation in SANAA's work, where they curate the type of subject inhabiting their spaces while also providing a space where said subjects curate their own lifestyle. The first mode occurs in projects such as the Seijo Townhouses where facing picture windows compel the residents into a curatorial lifestyle.

|

| Seijo Townhouses, Tokyo - SANAA |

The second may be seen in the Rolex Learning Center in Lausanne, Switzerland; a sparse undulating structure where "...the attention of inhabitants shifts to the aesthetic performance of their habitation."[3] Allen points out the similarity of this condition to the theatricality of minimalist art that Michael Fried contrasted with 'absorption'. Minimalist art displaces the focus from the work to the act of observation thus transforming the act into a kind of spectacle.

|

| Rolex Learning Center, Lausanne, Switzerland - SANAA |

Decomposition is evident in the de-emphasis of the program in SANAA's work and a focus on moments of habitation, however Sejima departs from Ito in her sense that individuals should continually be in contact with their urban surroundings, rejecting the cocoon-like nature of the Pao.[4] However in both cases, there is a fluid form of identity negotiation, whether in Ito's nomadism or Sejima's curation. These both resonate with the ideas advanced by Zygmunt Bauman within the framework of

liquid modernity, a description of the societal features of an increasingly turbulent late stage of modernity.[5] The liquid modern individual actively 'curates' their lifestyle amidst the choices presented by consumer culture leading to a kind of shifting, 'nomadic' existence. Ito and Sejima are both sensitive to the increasing intensity of the contemporary condition and seek to find a place for architecture in this floating world by setting the stages on which the negotiation of identity occurs.

Notes:

1. Iñaki Abalos and Juan Herreros, "Toyo Ito: Light Time," in

El Croquis: Toyo Ito, 1986-1995, no. 71, eds. Richard C. Levene and Fernando Márquez Cecilia (Madrid: El Croquis, 1995), pg. 36.

2. Matthew Allen, "Control Yourself! Lifestyle Curation in the Work of Sejima and Nishizawa," in

Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else, eds. Esther Choi and Marrikka Trotter (Cambridge, Mass: Work Books, 2010), pg. 24.

3. Ibid, pg. 29.

4. Koji Taki, "Conversation with Kazuyo Sejima," in

El Croquis: Kazuyo Sejima, 1988-1996, no. 77 (I), eds. Richard C. Levene and Fernando Márquez Cecilia (Madrid: El Croquis, 1996), pg. 9.

5. Zygmunt Bauman,

Liquid Modernity (Malden, Mass: Blackwell, 2000)

No comments:

Post a Comment